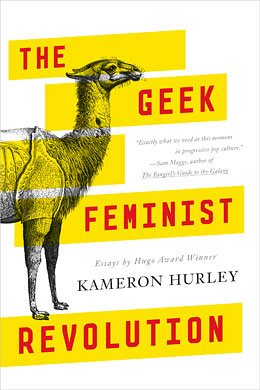

The Geek Feminist Revolution is a collection of essays by double Hugo Award-winning essayist and fantasy novelist Kameron Hurley—available May 31st from Tor Books!

Unapologetically outspoken, Hurley has contributed essays to The Atlantic, Locus, Tor.com, and others on the rise of women in genre, her passion for SF/F, and the diversification of publishing. The book collects dozens of Hurley’s essays on feminism, geek culture, and her experiences and insights as a genre writer, including “We Have Always Fought,” which won the 2013 Hugo for Best Related Work. The Geek Feminist Revolution will also feature several entirely new essays written specifically for this volume—including “Where Have All the Women Gone?” presented below.

Where Have All the Women Gone?

Reclaiming the Future of Fiction

“WOMEN DON’T WRITE EPIC FANTASY.”

If I had a dollar for every time some dude on Reddit said something that started with “Women don’t…”, I’d be so rich I wouldn’t be reading Reddit.

Erasure of the past doesn’t always follow a grand purge or sweeping gesture. There’s no great legislative movement or concerted group of arsonists torching houses to bury evidence (that’s usually done to inspire terror). No, erasure of the past happens slowly and often quietly, by degrees.

In her book How to Suppress Women’s Writing, science fiction writer Joanna Russ wrote the first internet misogyny bingo card—in 1983. She listed the most common ways that women’s writing—and, more broadly, their accomplishments and contributions to society—were dismissed and ultimately erased in conversation. They were:

1. She didn’t write it.

The easiest, and oftentimes the first appearing in conversation, is the simple “women don’t” or “women didn’t.” If delivered to an indifferent or ignorant audience, this is often where the conversation stops, especially if the person speaking is a man given some measure of authority. “Women never went to war” or “Women simply aren’t great artists” or “Women never invented anything” are common utterances so ridiculous that to refute them becomes tedious. As I grow older, I’ve ceased making long lists of women who, in fact, did. More often, I’ll reply with the more succinct, “You’re full of shit. Stop talking.” If, however, the person who says this is challenged with evidence that yes, in fact, women have and women do, and here are the examples and the lists, the conversational misogyny bingo moves on to…

2. She wrote it, but she shouldn’t have.

I hear this one about my own writing a lot, and I see it applied to romance writers and other outspoken feminists in particular. The writing is too sexual, too political, too feminist, or even— funny enough—too masculine to be real writing. This type of writing, because it is written by women, is considered somehow deviant or disorderly. It puts me in mind of those angered at the idea that science fiction is only good if it isn’t “political,” which is code for “does not reinforce or adhere to the worldview shaped by my personal political beliefs.” The reality is that all work is political. Work that reinforces the status quo is just as political as work that challenges it. But somehow this type of work is considered particularly abhorrent when it’s written by women.

3. She wrote it, but look what she wrote about.

Men, famously, can write about anything and be taken seriously. Jonathan Franzen writes books about family squabbles. Nicholas Sparks writes romance novels. Yet these same subjects, when written by women, are assumed to be of lesser note; unimportant. Jennifer Weiner is especially vocal about this erasure of the weight of her own work. Yes, she wrote it, they will say, but of course she wrote about romance, about family, about the kitchen, about the bedroom, and because we see those as feminized spheres, women’s stories about them are dismissed. There is no rational reason for this, of course, just as there’s no rational reason for any of this erasure. One would think that books by women written about traditionally women’s spaces would win tons of awards, as women would be the assumed experts in this area, but as Nicola Griffith’s recent study of the gender breakdown of major awards shows, women writing about women still win fewer awards, reviews, and recognition than men writing about… anything[1].

Writers of color also see this one in spades—yes, they wrote it, but it wasn’t about white people’s experiences. Toni Morrison labored for a very long time to finally get the recognition her work deserved. It took a concerted effort, complete with very public protest, to finally get her a National Book Award. Arguments were made that Morrison’s work was dismissed because she wrote about the experiences of black people. This type of erasure and dismissal based on who is writing about whom is rampant. While white writers are praised for writing about nonwhite experiences, and men are praised for writing about women, anyone else writing about the experiences of the people and experiences they know intimately is rubbed out.

4. She wrote it, but she wrote only one of it.

Few creators make just one of anything, including writers. It generally takes a few tries to get to that “one-hit” book, if one ever achieves it. We also tend to remember writers for a single, seminal text, as with Susanna Clarke’s massive undertaking, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. Yet Clarke also has a short story collection available—though few hear about it. Others, like Frank Herbert, write a number of wonderful novels but become known for just one great text, like Dune. Few would argue that Herbert only wrote one novel worth remembering, but I have checked this off on the bingo card listening to someone dismiss Ursula Le Guin because “she really only wrote one great book and that was The Left Hand of Darkness.” A lack of reading breadth and depth is on the reader, not the author. But one sees this applied most often to women writers. “Yes, that was a great book, but she only wrote one book, so how great or important could she really be?” one says, forgetting her twelve other books.

5. She wrote it, but she isn’t really an artist, and it isn’t really art.

Genre writers have contended with this one for years—men and women alike— but this excuse for dismissal is still more often used against women. Even within the genres, women’s work is skewered more often as being not “really” fantasy, or science fiction, or simply not “serious” for one reason or another. It’s a “women’s book” or a “romance book” or “some fantasy book with a talking horse for God’s sake” (I actually saw a female writer’s book dismissed this way after it showed up on the Arthur C. Clarke Award shortlist one year, as if whale-shaped aliens and time travel were any less ridiculous).

Women’s backgrounds are also combed over more than men’s, especially in geek circles, and you see this with the “fake geek girl” backlash, too. Is she a real engineer? Okay, but did she actually work for NASA or just consult for them? “Yes, she wrote a science fiction book, but it doesn’t have real science in it” or “Yes, she wrote a science fiction book but it’s about people, not science” are popular ways of dismissing women’s work as being not “really” part of the genres they are written in, or simply not real, serious art the way that those stories by men about aliens who can totally breed with humans are.

6. She wrote it, but she had help.

I see this one most with women who have husbands or partners who are also writers. Women whose fathers are writers also struggle with this dismissal. Rhianna Pratchett, a successful writer in her own right, finds her work constantly compared to her father Terry’s, and, coincidently, folks always seem to find ways her work isn’t as “good,” though Rhianna’s style and her father’s are completely different. For centuries, women who did manage to put out work, like Mary Shelley, were assumed to have simply come up with ideas that their more famous male partners and spouses wrote for them. The question “So, who really writes your books?” is one that women writers still often get today.

7. She wrote it, but she’s an anomaly.

The “singular woman” problem is… a problem. We often call this the “Smurfette principle.” This means that there’s only allowed to be one woman in a story with male heroes. You see this in superhero movies (there is Black Widow and… yeah, that’s it). You see it in cartoons (April, in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles). And you see it in awards and “best of” lists, typically but not always written by men, who will list nine books by men and one book by a woman, and that woman is generally Ursula Le Guin, Robin Hobb, or Lois Bujold. The singular woman expectation means that when we do see more than one woman in a group, or on a list, we think we’ve reached parity. Studies have shown that when women make up just 30 percent of a group, men and women alike believe there are an equal number of men and women in the room. At 50 percent women—a figure we see so little in media representation that it appears anomalous—we believe that women outnumber men in the group. What this means is that every woman writer is given an impossible task—she must strive to be “the one” or be erased.

When we start to list more than one female scientist (“Yes, there was Marie Curie” tends to be the answer when one asks about women scientists), or astronaut, or race car driver, or politician, we’re often accused of weighting women’s contributions more heavily than men’s. Though my essay “We Have Always Fought,” about the roles of women in combat, was largely well received, most criticism of the piece rested on this accusation: that by focusing on remembering and acknowledging the roles of women in combat, I was somehow erasing or diminishing the roles of men. “Yes, women fought,” the (largely male) commenters would admit, “but they were anomalies.”

8. She wrote it BUT. . .

The experiences I write about in my fantasy and science fiction novels tend to be very grim. My work comes out of the tradition of both new weird—a combination of creeping horror and fantastical world-building—and grimdark, a label most often applied to gritty, “realistic” fantasy that focuses on the grim realities of combat and a nihilistic “everything is awful” worldview. Yet when my work hit the shelves I was amused to see many people insist my work was neither new weird nor grimdark. There was too much science fiction, or not enough sexual assault against women (!) or too much magic (?) or some other “but.” Watching my own work kicked out of categories I was specifically writing within was a real lesson in “She wrote it but…” And lest you think categories don’t matter, remember this: categories are how we shelve and remember work in our memory. If we’re unable to give those books a frame of reference, we are less likely to recall them when asked.

I am still more likely to find my work remembered when people ask, “Who are your favorite women writers?” than “Who are your favorite science fiction writers?”

And that, there, demonstrates how categorization and erasure happen in our back brains without our conscious understanding of what it is we’re doing. Yes, I’m a writer, but…

When you start looking at reactions to the work of some of your favorite women writers, you will see these excuses for why her work is not canon, or not spoken about, or not given awards, or not reviewed. I could read a comment section in a review of a woman’s work, or a post about how sexism suppresses the cultural memory of women’s work, and check off all of them.

The question becomes, once we are aware of these common ways to dismiss women’s work, how do we go about combating them? These ways of disregarding our work have gone on for centuries, and have become so commonplace that men are used to deploying them without challenge as a means to end all debate.

I’d argue that the easiest way to change a behavior is first to become aware of it. Watch for it. Understand it for what it is. And then you must call it out. I’ve taken to typing “Bingo!” in comments sections when these arguments roll out, and linking to Russ’s list. When we see sexist and racist behavior, the only way to change that is to point it out and make it clear that it’s not okay. The reason people continue to engage in certain types of behaviors is because they receive positive feedback from peers, and no one challenges them on their assertions. If we stop swallowing these excuses, and nodding along when people use them, we take away the positive reinforcement and lack of pushback that’s made it possible for them to use these methods of dismissal.

Because I write such dark stories, many people think that I’m a pessimistic person. But that’s not true. I’m a grim optimist. I understand that the road to a better future is long and bitter and often feels hopeless. Yes, there is a warm gooey core of hope I carry with me at the very center of myself, and it is the hope of someone who knows that change is difficult, and feels impossible, but that even a history that has suppressed and erased so much cannot cover up the fact that change is possible.

[1] Nicola Griffith,“Books about Women Tend Not to Win Awards”.

Excerpted from The Geek Feminist Revolution © Kameron Hurley, 2016

Thanks for this. :)

Wonderful piece – and so sad that we still need to have this conversation. For some reason the sci-fi/fantasy environment seems to be a lot more regressive than other fields. I’m an art historian, a notoriously conservative field, and while the issue of women who were/are artists are debated, sometimes vigourously, the issue isn’t being so aggressively dismissed as I’ve seen in among the sci-fi/fantasy fandom.

I wish I could think of something smart and snappy to say, but wow, just wow, is all I’ve got. Loved the ‘grim optimist’ thing.

One day, one day, work will be judged solely on its merits and nobody will give a damn what was the gender (color, orientation, whatever other biases may exist) of the artist who created it.

Unfortunately, that day won’t be tomorrow.

Thanks for an enlightening and interesting essay; this kind of work helps bring one day a bit closer, I hope…

zdrakec

At the time I first commented I didn’t have a bunch of time to say anything intelligent to the conversation but I did want to say

1)I love your grim optimism description and often describes my frame of mind (although I admit to being heavily influenced by Tolkien as well in that regard)

2)While reading point 3 I found myself nodding as two of my favorite genre authors are Sharon Shinn and Juliet Marillier but I’ve noticed in the past I’ve been reticent at recommending them (especially to males), or usually with the caveat, ‘Well, their works do tend to focus more on romance’ or something of that nature – even though many other things about their works are great.

Funny. Five minutes before reading this, I’d just read a local newspaper column about how it might be a good idea to try to be more forgiving, more gentle – without giving up being critical, analytical etc. The column ended with the note “give praise to a woman a day [about their accomplishments]”. Ten of the first commentators of the column had read this as “don’t you dare ever give praise to men”…

@6

Why is it that some men react that way? As if acknowledging women’s accomplisments is a zero sum game that means men won’t be acknowledged. Why are some men so scared of this? I just don’t get it.

“If I had a dollar for every time some dude on Reddit said something that started with “Women don’t…”, I’d be so rich I wouldn’t be reading Reddit.”

See, that’s not thinking like a winner. If I had a dollar for every time some dude on Reddit said something that started with “Women don’t…”, I’d be rich enough to buy Reddit, which I would then mold towards encouraging people to post “women don’t” type comments and make even more money!

But seriously, another note on #3 is how often women, one way or another, get steered toward (or out of) certain categories. I don’t think there are less women interested in writing hard SF than there are men (well, maybe a little if you total up the cultural baggage that discourages them from STEM fields for example, but not enough to make up for the disparity)… but I certainly believe that they’re discouraged, recommended towards fantasy, recommended towards YA (not that there’s anything wrong with these fields either, of course, but the point is people will get nudged to where they’re already more accepted). Editors may, even subconsciously, be less likely to buy a hard SF novel by a female writer with “even if it’s great it won’t sell as well because men who read hard SF are less likely to try a female author.” Agents may know this too and suggest they try different fields. That’s the thing about biases, even small biases can multiply their effects when you have a lot of people with them.

I do have to admit that when I review I do sometimes fall a little into the “But it’s about a talking horse” category… not saying it’s intrinsically less valuable for that, but because… that’s really not the types of stories I’m personally interested in, on the whole. I’m also not interested in Brian Jacques Redwall series (I remember my brother once was given a Redwall book and being both a SF/Fantasy reader, prolific enough to rarely turn down books, mentioned to me later something like, “I thought I pretty much liked anything fantasy or SF… but turns out talking $@@@@@!$ing animals are where I draw my line.”) either. Certain things just generally aren’t my thing. I’m not trying to pull the “it’s not REALLY sexist all the time” card, but if it is (and it may well be that my early tastes were shaped in some ways by cultural attitudes about the relative values of different tropes, and that I for some reason notice it more when female authors use it), it’s buried deep and subconsciously at level I may not be able to change. I try to keep it at a “this is a personal distaste” level rather than “this is objectively less quality” at least. And while I may have commented on, and counted as a negative, the presence of magic or magic-like abilities (even if with some low level of scientific handwave, it wasn’t enough of one to not count as a drawback for me) in Hurley’s own works once or twice (the Bel Dame stories which is all I’ve read of hers so far)… I kept reading the whole trilogy despite that because they were still damn engaging books and well worth reading.

While reading the Hugo nominations – I’m trying to judge the story for the story.

I’m annoyed with some details in each of the novels I’ve read so far. But I’m trying to figure out if I’m being more forgiving of the authors because of factors outside of the book.

Uprooted – annoyed by how often the phrase “and then” is used. This is rater a small problem. I think a major relationship is poorly developed. One more edit, and the book could have achieved true greatness.

The Aeronaut’s Windlass – annoyed by the world building – it’s bi-polar. This is a rather large problem. One of the relationships is rather poorly developed. It’s the start of a larger story. It’s a fun read, but nothing of true greatness.

But which do I judge superior?

I fear many others will judge Windlass superior because they have a more establish relationship with the author.

And this leads to the problems address above. :-(

The link in the footnote at the end of the article is broken. There is a space between “about” and “-women” which needs to be closed.

@10: The link should be fixed now–thanks!

I’ve read thousands of science fiction and fantasy novels over more than 40 years and I have never considered the sex of the author as part of my decision making process as to whether to buy the book or in my critique of it.

In fact, I don’t personally know a single person who is a reader of these genres that is biased against women authors or judges the quality of the effort with gender in mind.

I can’t speak for the community at large, obviously, but my little corner of the reading world sees no difference between a male and female author.

6. She wrote it, but she had help.

see the Coen Brother’s brilliantly weird Barton Fink for a brilliant reversal of this.

and thanks for the essay in general. I’m sharing.

“some fantasy book with a talking horse for God’s sake”

So like The horse and his boy? one of the best books in the Narnia series? I am sure no one today would question C.S. Lewis choice of using a talking horse. Isn’t fantasy partly about the wondrous and fantastical how can you even Use that as an argument why it shouldn’t be real fantasy.

@14 – hah, right. I got the impression we were supposed to know which book she was talking about but that was the only one I could think of, and obviously that wouldn’t be it. Which book was she talking about, does anybody know?

@14 & 15: There is always Mercedes Lackey and her Valdemar series.

But I’m not sure what book is being referred too. I looked up the Clarke Awards, but I’m not familiar enough with the books to know which one it is, without more research than I’m willing to put forth.

@14-16: The book being referred to is The Waters Rising by Sheri S. Tepper.

@12: Congratulations on being 100% bias free over 40 years of reading! That is indeed something to brag about, since I assume you mean both conscious and unconscious biases! I can’t claim that, even though I try my best. And even more remarkable that everyone you know is the same way. But yes, obviously, you can’t speak for the community since the stats don’t bear out a lot of other people being that way since the numbers are so skewed, where women get published less, and promoted less, and recommended less. Unless you believe that women are just naturally much less talented or inclined, your bias-free little corner of fandom truly is something of a miracle.

But you know, you can still be contributing to the problem. Not deliberately, I mean. I’d never imply that. But simply through completely innocent actions that, in aggregate and in a world that is not as enlightened as you and your corner, can magnify the inequalities.

For example, presumably, at least for a lot of your early reading life, and maybe still today, you read mostly books that were published by a big publisher. Nothing wrong with that. May have been your only option. And you don’t consider gender of the author at all… but they did. Maybe they were 2 times more likely to publish a man than a woman, even counting out every other bias that they unconsciously magnified (fewer women submitting, etc, etc), just because they thought women wouldn’t sell. So since your chance of picking up any given book you saw on the shelf was 50/50 split based on gender, if there were twice as many men published, then 66% of the time you’d be selecting male authors. If you read thousands of books, you still only read hundreds of women authors. You didn’t consider the gender, you let the publisher do that for you.

Or maybe, when you see any book, you read the synopsis, and if it sort of grabs you but isn’t immediately a “I must read this now” book, you decide… “I’m going to wait, maybe if I hear good things, I’ll pick it up.” Absolutely nothing sexist about that, it’s a neutral assessment that depends nothing on gender… your conscience is clear. But… if a lot of other people ARE a little bit sexist, and that book’s by a woman? Statistically speaking, you’ll hear much less good things. Not necessarily because of people being outright more critical (though that happens too), they may just be less likely to give it a try. So it might get forgotten entirely and drift quietly out of print. Meanwhile, a book by a man, picked up by a buddy of yours who is pretty easy to please but just a little bit unconsciously, quietly sexist, well, he raves about that one, while he passed over the book by a woman. Wait, I’m sorry, your little corner’s all bias free. Well, a friend of one of your friends then, and your friend hears the rave, picks it up, and passes the rave on to you. Over time, a lot of authors get recommended this way, some female, some men… but… statistically, less women than men, even factoring in everything else. And it doesn’t just stop with people who recommend to you and your friends, because they’re talking to many others, and when awards come by, more men get mentioned, and when best of lists get created, the men are more prominently placed. You didn’t consider the gender, you let the grapevine do it for you.

Or maybe you don’t consider gender… but you don’t want to read a book that’s all romance. You don’t mind if there’s some, certainly, but you don’t want that to be the whole point. Nothing sexist there, just your personal tastes. So you pick up a book and look at the cover and read the description. Ah, great, a giant worm rising up over a tiny human figure in the desert. Sounds exciting. Back talks about an interstellar empire and trading in spice. And sure, there’s a love interest in the story. You don’t necessarily see this from the description, but from reading, you find that the hero finds someone he loves but has to marry a princess for political reasons, while keeping his love as a concubine officially. Except, what you don’t realize is that if a woman wrote that exact same story, they might have sexistly decided that women are more likely to read women authors, and so play up the aspects that they believe appealed to women… the cover might have been a man and woman embracing in the desert, and the description might have played up that he must choose the love of his life or the princess that will keep the planet together, or a cheesy slogan like “His family traded in spice… but was she more spice than he could handle?” And it’s not on the cover, but maybe something about riding powerful worms is mentioned in the back, but you’re not sure if that’s some kind of double entendre. Sounds like romance, maybe even smutty romance, so give it a pass. Who knows how many authors you passed up because they weren’t marketed towards your tastes, but if they were more likely to be women, then you’re reading even less of them. You didn’t consider the author’s gender, you let the marketing department do that for you.

And these stack. Because you read less women, because less women are published and marketed differently, you’re less likely to recommend them to your friends who might be on the fence about a book and waiting for a recommendation, than you are male authors.

If there are biases in the world outside of you, and statistics seem to indicate that there are, a-plenty, not considering the gender of the author just blinds you to them. Maybe you shouldn’t choose an author based on their gender, or critique them differently… but you might want to at least notice so you can pay attention to what biases are in play before you even cracked open the book, and maybe see through them, a little.

@18 ghostly1

*wild applause*

Thank you, Kameron, for this post. I just tweeted it.

Full disclosure: I am a cisgender woman who used to be a scientist (I have a master’s degree in physics). I changed fields and earned a Ph.D. in English and teach college composition and literature, including classes on Science Fiction. When I was still in the sciences, I worked on a NASA-funded satellite (which is now, sadly, space junk) and as an operator for a nuclear accelerator. My master’s thesis was on teaching relativity theory in the undergraduate classroom. I am also a self-proclaimed geek who lists “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy and “The Time Machine” among my favourite books. SF is one of my major areas of critical work. So I at least *kind* of know what I’m talking about.

I NEVER saw one of my scientific male colleagues being asked to defend their “cred.” I have NEVER been asked why there aren’t more male scientists or male writers of science fiction. I’ve NEVER been challenged to come up with the name of a man to prove that men can write science fiction as well as women.

What HAS happened:

I HAVE seen my female colleagues in the sciences sexually and emotionally harrassed for the egregious crime of being, well, women. Every time I teach a science fiction course, I HAVE been asked if women can really write science fiction. I HAVE had students who literally cannot believe that I used to be a scientist and try to “catch me out” by quizzing me. I HAVE memorized a list of female science fiction authors so I have something to say when people ask me why women don’t write science fiction (for anyone who is interested: Mary Shelly, Katharine Burdekin, C. L. Moore, James Tiptree, Ursula K. LeGuin, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Margaret Atwood, Caitlin R. Kiernan…this isn’t actually the full list but I will stop boring everyone now).

I am sorry if this comment comes off as a little ranty. It’s just that, like many women, I’ve been dealing with this stuff for *my entire life.* I’m not a Manic Pixie Dream Girl nor am I Marie Curie. And, outside of those categories, there aren’t a whole lot of other places to “be” as a geek, a woman, an SF fan/scholar, and a feminist

@12 funny you should say that. I haven’t ever considered the gender of the author in the novels I have chosen to read and I thought the split between male and female was relatively equal.

Last week, I decided to determine the actual ratio. Luckily, I track all the books I read in a database so it was easy to categorize the roughly 1500 novels [mostly SF&F] i have read over the past decade or so.

It was not equal. It was nowhere close to equal. Women wrote only 24% of the novels I have read. Interestingly, I have read on average 3.6 books from each woman but only 3.0 from each man. I’m not entirely certain what to draw from that but it is a notable difference in my reading patterns. Perhaps it indicates I am more likely to pick up a book by a male author regardless of actual quality.

@21: Maybe six of one, half a dozen of another? Yes, it *could* mean that you are more likely to gravitate towards SF books by men. I *could* also mean that there are a HECK of a lot more easily-available books out there, especially in the SF genre, that have been written by men.

My infamous go-to example is Caitlin R. Kiernan, a contemporary female writer of SF, including hard sci-fi. She has a master’s in vertebrate paleontolgy and REALLY knows her stuff, scientifically. While she’s not exactly unknown, she’s also not super easy for the casual or even not-so-casual reader to always find. I personally would put her work up there with Ray Bradbury or even, dare I say it, much of Isaac Asimov. However, the former two male writers are super-easy to find in bookstores or online. Despite her dedicated fan base, Kiernan is not. As far as I know, there has been no “academic” critical work published on her writing, such as in PMLA (I am trying to change that!). I am *certainly* the only person at my school who teaches her work. I do not think that I work with a department full of sexists or in a profession full of sexists, but it can be a kind of “domino” effect in which the “canonical” writers continue to be canonical because they’ve ALWAYS been canonical…and we’ve all ALWAYS lived in Shirley Jackson’s castle, too. *shudder*

PS: To anyone looking for hard sci-fi by Kiernan, I recommend her short-story collection, “A is for Alien.” I personally think her best work to date (which I guess I’d have to say is SF, but is mostly unclassifiable) is “The Drowned Girl.”

PPS: When talking about identity politics regarding Kiernan, it can get even more complicated because she identifies as Queer as well

Glad to see some love for Kiernan as I really enjoy her work. “The Drowning Girl” os brilliant and daring in its form. I also really liked the creeping alien horror and the play with an unreliable narrator in “The Red Tree”. I enjoyed “Silk” and “Threshold” as well though I didn’t much care for the sequels.

I’ve read a few of her short stories but will now try to find “A is for Alien”.

YAY!!!! Another Kiernan fan! :D

I too didn’t love “A Murder of Angels” and “Daughter of Hounds,” the sequels to “Silk” and “Threshold,” respectively. (Although “Low Red Moon” wasn’t too bad…) I feel like Kiernan was trying to work through something, personally and artistically, especially with “A Murder of Angels.”

Kiernan works a lot with Subterranean Press but their books go out of print very quickly. She has a “Best-Of” collection out in two volumes “Two Worlds and In Between” that I believe you can buy on Amazon. I also recommend her hard SF novella “The Dry Salvages” and her short story collection “The Ape’s Wife” if you are looking for science fiction. (I’m pretty sure that the former is in her first “best-of” collection.)

I honestly think “The Drowning Girl” is one of the best novels I have ever read, and I read a LOT.